“Teaching, may I say, is the noblest profession of all in a democracy.”

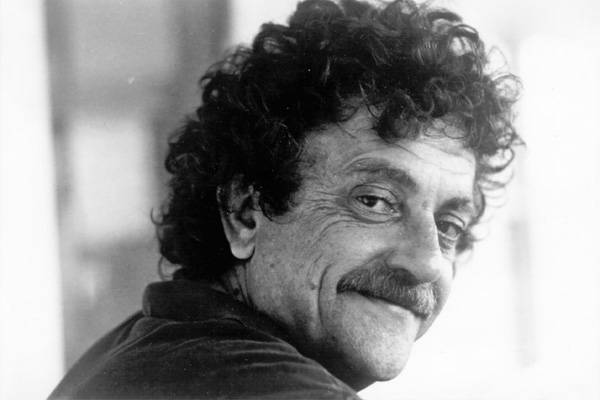

Kurt Vonnegut was a man of discipline, achampion of literary style, a kind of modern sage and poetic shaman of happiness, andone wise dad. After the publication of his now-legendary 1969 satirical novelSlaughterhouse-Five, Vonnegut added another point of excellence to his résumé: He became one of the country’s most celebrated and sought-after commencement speakers, and like other masters of the genre — includingNeil Gaiman, David Foster Wallace, Debbie Millman, Anna Quindlen, Bill Watterson,Joseph Brodsky, and Ann Patchett — he bestowed his gift of wit and wisdom upon throngs of eager young people entering the so-called “real world.”

If This Isn’t Nice, What Is?: Advice to the Young (public library) collects the graduation addresses the beloved writer delivered at nine different colleges over the quarter century between 1978 and 2004, among which are his poignant and heartening remarks to the women of the graduating class at Agnes Scott College in Decatur, Georgia, delivered on May 15, 1999 — the speech from which this entire collection borrows its title.

With his signature self-deprecation, Vonnegut reflects on the gift of compassion and how we — as a civilization, a culture, and as individuals — have failed it:

I am so smart I know what is wrong with the world. Everybody asks during and after our wars, and the continuing terrorist attacks all over the globe, “What’s gone wrong?” What has gone wrong is that too many people, including high school kids and heads of state, are obeying the Code of Hammurabi, a King of Babylonia who lived nearly four thousand years ago. And you can find his code echoed in the Old Testament, too. Are you ready for this?“An eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth.”A categorical imperative for all who live in obedience to the Code of Hammurabi, which includes heroes of every cowboy show and gangster show you ever saw, is this: Every injury, real or imagined, shall be avenged. Somebody’s going to be really sorry.

Though Vonnegut described himself as a Humanist — a secular set of beliefs to which Isaac Asimov also subscribed as an alternative to religion — and even called himself an atheist in another commencement address, he points to the story of Jesus Christ not as a religious teaching but as a cultural narrative that bequeaths a valuable moral disposition:

When Jesus Christ was nailed to a cross, he said, “Forgive them, Father, they know not what they do.” What kind of a man was that? Any real man, obeying the Code of Hammurabi, would have said, “Kill them, Dad, and all their friends and relatives, and make their deaths slow and painful.”His greatest legacy to us, in my humble opinion, consists of only twelve words. They are the antidote to the poison of the Code of Hammurabi, a formula almost as compact as Albert Einstein’s “E = mc2.”

Vonnegut makes sure his disposition toward religion isn’t misunderstood and the religiosity of these tales doesn’t obscure his larger point:

I am a Humanist, or Freethinker, as were my parents and grandparents and great grandparents — and so not a Christian. By being a Humanist, I am honoring my mother and father, which the Bible tells us is a good thing to do.But I say with all my American ancestors, “If what Jesus said was good, and so much of it was absolutely beautiful, what does it matter if he was God or not?”If Christ hadn’t delivered the Sermon on the Mount, with its message of mercy and pity, I wouldn’t want to be a human being.I would just as soon be a rattlesnake.Revenge provokes revenge which provokes revenge which provokes revenge — forming an unbroken chain of death and destruction linking nations of today to barbarous tribes of thousands and thousands of years ago.

This disposition, Vonnegut argues, is a personal choice, an individual moral obligation, something to cultivate within ourselves — even it means going against the cultural current:

We may never dissuade leaders of our nation or any other nation from responding vengefully, violently, to every insult or injury. In this, the Age of Television, they will continue to find irresistible the temptation to become entertainers, to compete with movies by blowing up bridges and police stations and factories and so on…But in our personal lives, our inner lives, at least, we can learn to live without the sick excitement, without the kick of having scores to settle with this particular person, or that bunch of people, or that particular institution or race or nation. And we can then reasonably ask forgiveness for our trespasses, since we forgive those who trespass against us. And we can teach our children and then our grandchildren to do the same — so that they, too, can never be a threat to anyone.

He then turns an optimistic eye toward the creative arts — the music, painting, literature, film, theater, and all the humane ideas that “make us feel honored to be members of the human race” — urging the graduating women to consider how they would contribute to that world and offering them a gender-appropriate revision of Robert Browning’s famous line, replacing his word “man,” an old-timey linguistic convention denoting a human being, with “woman”:

A woman’s reach should exceed her grasp, or what’s a heaven for?

Vonnegut turns to the nature of human relationships and what he considers to be the only true source of friction for lovers, often mistaken for more superficial motives:

You should know that when a husband and wife fight, it may seem to be about money or sex or power.But what they’re really yelling at each other about is loneliness. What they’re really saying is, “You’re not enough people.”[…]If you determine that that really is what they’ve been yelling at each other about, tell them to become more people for each other by joining a synthetic extended family — like the Hell’s Angels, perhaps, or the American Humanist Association, with headquarters in Amherst, New York — or the nearest church.

This, in fact — this passionate advocacy for the value of community, of finding your tribe — is something Vonnegut reiterates across his many commencement speeches. In another address, he, the father of seven children, argues that the modern family is simply too small, leaving too much room for loneliness and boredom, and advises: “I recommend that everybody here join all sorts of organizations, no matter how ridiculous, simply to get more people in his or her life. It does not matter much if all the other members are morons. Quantities of relatives of any sort are what we need.” Such counsel seems, in hindsight, particularly at odds with something else he proclaimed when he stood before the women of Agnes Scott College that spring afternoon in 1999:

Computers are no more your friends, and no more increasers of your brainpower, than slot machines…Only well-informed, warm-hearted people can teach others things they’ll always remember and love. Computers and TV don’t do that.A computer teaches a child what a computer can become.An educated human being teaches a child what a child can become. Bad men just want your bodies. TVs and computers want your money, which is even more disgusting. It’s so much more dehumanizing!

The latter, of course, is something only a man can say — but given what a warm-hearted and thoughtful man Vonnegut was, the safe and decent thing to do would be to attribute such a well-meaning but ignorant remark not to ill intent but to his all too deeply engrained Y chromosome, or more precisely to hishaving unwittingly swum with the current his whole life.

More importantly, however, it’s interesting to consider that Vonnegut — writing in 1999, before Facebook and Twitter and most current thriving online communities existed — so readily dismisses the connective potentiality of “computers” (and even advises those women who may want to pursue motherhood to “keep that kid the hell away from computers… unless you want it to be a lonesome imbecile”) while in the same breath urging us to seek out “a synthetic extended family.” He even admonishes: “Don’t try to make yourself an extended family out of ghosts on the Internet. Get yourself a Harley and join the Hell’s Angels instead.” One ought to wonder how Vonnegut might feel if he were alive today to witness many of these initially online-only “ghostly” connections blossom into deep and real relationships offline, the best of them of the lifelong kind.

A curmudgeonly celebrator at heart but a celebrator above all, Vonnegut then returns to his optimistic vision for these young women’s lives:

By working so hard at becoming wise and reasonable and well-informed, you have made our little planet, our precious little moist, blue-green ball, a saner place than it was before you got here.[…]Most of you are preparing to enter fields unattractive to greedy persons, such as education and the healing arts. Teaching, may I say, is the noblest profession of all in a democracy.

(A necessary aside here: If any of Vonnegut’s words to the young women appear patronizing, this is more a function of the genre than of the man: Lest we forget, the basic rhetoric of the commencement address is one where a patronly “father figure” (or a matronly “mother figure”) gets up in front of a green crop of young minds and proceeds to dispense wisdom on how to live — wisdom that comes from a hard-earned, know-better place of having lived it himself or herself. The very point of a commencement address, it’s safe to say, is to be willingly patronized.)

Vonnegut’s closing remarks are, perhaps unsurprisingly, a gladdening celebration of books and reading:

Don’t give up on books. They feel so good — their friendly heft. The sweet reluctance of their pages when you turn them with your sensitive fingertips. A large part of our brains is devoted to deciding whether what our hands are touching is good or bad for us. Any brain worth a nickel knows books are good for us.

He concludes with a wonderful anecdote about his Uncle Alex, from which this entire collection borrows its title:

One of the things [Uncle Alex] found objectionable about human beings was that they so rarely noticed it when they were happy. He himself did his best to acknowledge it when times were sweet. We could be drinking lemonade in the shade of an apple tree in the summertime, and Uncle Alex would interrupt the conversation to say, “If this isn’t nice, what is?”So I hope that you will do the same for the rest of your lives. When things are going sweetly and peacefully, please pause a moment, and then say out loud, “If this isn’t nice, what is?”

And just to drive his point home in the most heartfelt way possible, Vonnegut ends with a soul-warming exercise:

That’s one favor I’ve asked of you. Now I ask for another one. I ask it not only of the graduates, but of everyone here, parents and teachers as well. I’ll want a show of hands after I ask this question.How many of you have had a teacher at any level of your education who made you more excited to be alive, prouder to be alive, than you had previously believed possible?Hold up your hands, please.Now take down your hands and say the name of that teacher to someone else and tell them what that teacher did for you.All done?If this isn’t nice, what is?

If This Isn’t Nice, What Is? is a spectacular read in its entirety, brimming with Vonnegut’s unflinching convictions and timeless advice to the young. Complement it with more of history’s greatest commencement addresses, including Anna Quindlen on the essential ingredients of happiness, David Foster Wallace on the meaning of life, Neil Gaiman on the resilience of the creative spirit, Ann Patchett on storytelling and belonging, and Joseph Brodsky on winning the game of life, Debbie Millman on courage and the creative life, and Bill Watterson on not selling out.

No comments:

Post a Comment