________________________________

In his landmark work Principles of Bibliographical Description, issued in 1955, Fredson Bowers scoffed:

"The craze for first impressions of first editions, and first issues of first impressions of first editions, and first states of first impressions of first editions, has occasionally resulted in speculation and bibliographical absurdity among collectors and dealers.... Any minor change made in the course of the original printing is immediately seized on as constituting an 'issue.' A trial binding used for perhaps twenty copies of salesmen's samples becomes a rare 'first issue.'"

But as anyone who has read him knows, Professor Bowers was a cantankerous old blowhard. (And, I have it on authority, notoriously slow to reach for the check at dinner. Just saying.)

"Edition," "impression," "issue," and "state" are terms with very precise bibliographical definitions, to be sure (for a concise discussion, see Terry Belanger's essay, "Descriptive Bibliography," pp. 97-99, in Jean Peters' Book Collecting: A Modern Guide). But for the modern collector, "first issue" is, for all intents and purposes, synonymous with "first edition," and when it comes to edition, First is King.

So. Let's pretend, for a moment, that you're a book. Let's pretend you're a very lucky book. You have been blessed with an editor with impeccable taste, a proofreader with an eagle eye, a printer whose inks are clear and true, a binder who checks his work not twice but thrice, and, most of all, an author who never, EVER, changes his mind.

You are, in all respects, PERFECT.

Yes. Well, that's that then.

Now let's pretend you're kind of, well, an ordinary book. Your editor has two kids under the age of three at home and hasn't slept in six months; your proofreader had a couple too many at bingo last night; your printer sometimes mistakes the green ink for the blue, or vice-versa; your binder has so many jobs waiting in the queue that he considers it a moral victory when he manages to get the title page bound in somewhere near the front half of the book; and your author just had a fight with her husband and, halfway through the print run, has decided to dedicate you, you poor abused, luckless tome, to the local cat rescue facility, instead.

Which brings us to the "points of issue."

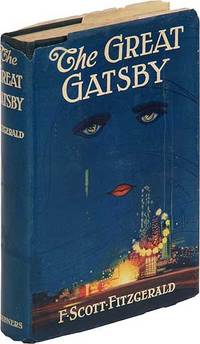

First edition of The Great Gatsby

This means that those earliest copies - the ones with the typos, the heavier-weight paper, the incorrect dust-jacket - are out there in the wild, ripe for the picking by the astute collector who knows that the true first issue of Ben Hur is dedicated "To The Wife of My Youth." (Later issues were re-dedicated "To The Wife of My Youth - Who Still Abides With Me" after Lew Wallace received thousands of letters of condolence - and not a few marriage proposals - from fans who thought that Susan Wallace - still very much alive - had died.)

Famous examples of first-issue "points" include...

- A plethora of typos in Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby (as well as a missing blurb on the rear panel of the dust jacket)

- A missing dedication page in Salinger's Raise High the Roof Beams Carpenters (later issues have the dedication page tipped in, hastily and wastily, at random spots)

- Hemingway's Men Without Women has a number of points of issue, including a paper change which resulted in the earlier issue being heavier (printed on 80# paper) - so that copies printed later weigh only 15.8 ounces apiece.

More Resources for Points of Issue

There are field guides that can help you sort the wheat from the chaff, such as Bill McBride's Points of Issue and Allen and Patricia Ahearn's Collected Books, and of course there's much useful (though sometimes misleading - caveat emptor!) information on the Internet.

But sometimes a full-on author bibliography is called for. For instance, the Ahearns' guide will tell you about the addition to the wording in the dedication to Ben Hur. What they neglect to mention is that the first edition of the book (with the 6-word dedication) went through no fewer than 5 (or possibly 6!) different binding cloths, colors, and styles; at least 3 different states of the advertisements (bound in at the rear); and 2 different states of the title page. For that information, you need to turn to the definitive Wallace bibliography, the dauntingly titled Bibliographical Studies of Seven Authors of Crawfordsville, Indiana: Lew and Susan Wallace, Maurice and Will Thompson, Mary Hannah and Caroline Virginia Krout, and Meredith Nicholson, by Dorothy Ritter Russo and Thelma Lois Sullivan.

And, though Professor Bowers might be left cold by "These works [which] ... are a series of signposts leading the collector from 'point' to 'point' of the correct state of the impression to purchase," in this case, the collector (or dealer) might be forgiven for wanting to know the difference.

Because when it comes to market, a first edition Ben Hur with the correct dedication, title page, advertisements, and the pretty china-blue floral binding is an entirely different animal, price-wise, than all the rest!

Author Bio:

Formerly the founder and manager of the now-defunct Rare Books Department at Barnes & Noble, Cynthia Gibson is currently engaged in an exciting new venture,BookFairs.com, which she hopes not to drive to a similar end. Further details of her sketchy life history can be found on her personal web site, CynGibson.com. She is eager to be reached at editor@bookfairs.com.